It has taken me a long, long time to write this post – now at least five or six days overdue! I apologize for the delay and hope you enjoy it:

Ukraine’s M-05 highway winds out of the center of Kyiv and heads south. If one can stand the near-constant rattle of car wheels against long-neglected potholes, nausea-inducing swerves to avoid runaway trucks or drivers who have forgotten about their turn signals, and perhaps the occasional wild animal – lane hog takes a literal meaning in this land – the highway will take you all the way to the Black Sea port of Odessa, a distance of nearly 500 kilometers.

On a clear day, scenery along the M-05 mimics Ukraine’s blue and yellow flag; wide open sky meets endless fields of golden wheat in a continuously looping landscape. The commonly-held idea of Ukraine as the breadbasket of Europe is hard to refute as field after field rolls by. This past Sunday, October 2, I looked out the car window as the sun rose over the road and finally began to comprehend the vastness of this country. My academic advisor, Vitaly played opera arias on the stereo as his colleague from Southern Connecticut University, Corinne, sat behind the wheel of her rented Volkswagen as we plodded out of the capital.

“Corinne, how can you stand driving here? I would go crazy.”

“I drive in Manhattan. This is so much better.”

I am still reluctant to believe her.

Wheat field after wheat field, truck after truck. And then a bus, filled with Hasidic Jewish men, their heads covered with tallitot, or prayer shawls, t’fillin, or phylacteries wrapped around their arms and foreheads. And another bus. And another. And another. And another.

It might surprise you, but we were actually all headed to the same place. Not Odessa, no. Indeed, Vitaly and Corinne were headed to the Black Sea later that day but I was not to join them for this part of the trip. I was in on the trip for a pit stop of sorts. For most of my readers, the name of this “pit stop” destination – Uman – likely means very little. But the time I spent there was the most eye-opening experience I have had in Ukraine to date – and may ever have anywhere in my life. And yes – there were thousands (THOUSANDS) of Hasidic Jews.

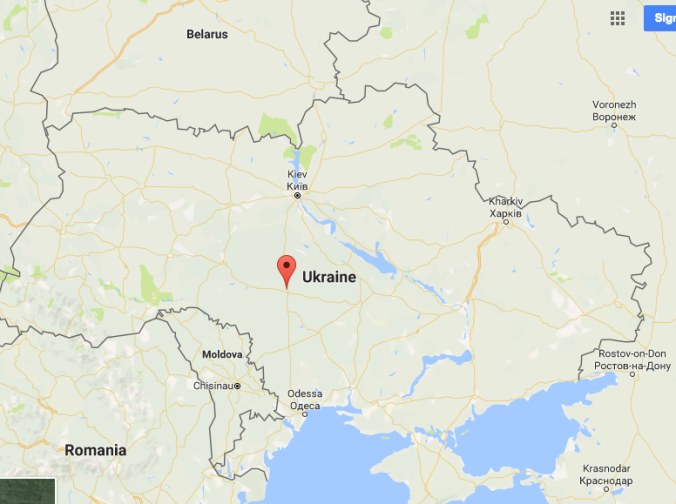

Screenshot from Google maps. Uman is marked with the red pin.

Let me explain (as best as I can – I am no expert on the historical and religious context that I feel is central to this post but I will do my best to be comprehensive and concise. Well, at least comprehensive.)

A typically sleepy city of less than 100,000 people, Uman for many people is little more than another place to pass through. Nestled in Ukraine’s Cherkasska Oblast’ (an oblast’ is a federal region), Uman is perhaps most famous in Ukraine for its Sofiyivka Park, one of the “seven wonders of Ukraine,” a UNESCO heritage site, and a testament to 18th century landscape design like that found at Versailles.

For some, however, Uman is famous in another way entirely. On the Jewish New Year, Rosh Hashanah, Uman transforms into a site of holy pilgrimage for tens of thousands of Hasidic Jews, the vast majority of whom are men, from around the world. Hoards of worshippers from Israel, the United States, France, Canada, and other corners of the globe descend on this little city to pray at the graveside of Rebbe Nachman of Breslov, an act believed to cleanse the souls of pilgrims during the Jewish High Holy Days – a time for reflection, forgiveness, and absolving of one’s sins before God.

A sign reads ‘Welcome’ in Hebrew as Corinne drives us into Uman.

Rebbe Nachman of Breslov (1772-1810) is considered the founder of the Breslov branch of Hasidic Judaism, named for the town in Ukraine where he spent a large amount of his time. He was born in Medzhibizh, a small town in Western Ukraine that was also home to his great-grandfather, the Baal Shem Tov (~1700-1760), or Besht, considered the founder of Hasidic Judaism. The Besht was a mystical Rabbi and scholar of Torah who believed in the development of a close rapport with God through everyday actions, conversations, and practices. There are many active branches of Hasidic Judaism alive today, most of which are named for the locations (mostly Ukrainian) where they were founded. The largest is the Lubavitcher group, best known for its ties to the international Chabad movement (also active in Claremont, CA – shoutout to the Matusof family!) now headquartered in…drumroll please…Brooklyn.

Continuing and building on the teachings of his great-grandfather, Rebbe Nachman generated a following as a tzaddik, or spiritual master. He was famous for his lessons, stories, and other teachings that attracted the attention of Jews all across Eastern Europe. His legacy remains vibrantly alive today and Breslover Hasidim are known for the emotional and spiritual intensity of their expressions of faith. An offshoot of the Breslovers, known as the Na Nachs, are famous for singing a song with the lyrics Na nach nachma nachman meuman. And they don’t just sing it. When I was in Israel in 2009, I distinctly remember walking around the holy cities of Jerusalem and Tzfat hearing people chant the words of this song, jump up and down in circles, and blast the tune from loudspeakers in the middle of the street. Little did I know I would “visit” the great Rebbe himself almost seven years later.

Rebbe Nachman died of tuberculosis at age 38 in Uman where he was later buried. Why people come to visit his grave to this day is best explained from an excerpt on the official website of the Breslov Hasidic group: (http://www.breslov.org/breslov-faq/#11)

“Rebbe Nachman made a promise no other Tzaddik in the whole of Jewish history has ever made. Taking two of his closest followers as witnesses, he said: `When my days are ended and I leave this world I will intercede for anyone who comes to my grave, recites the Ten Psalms of the Tikkun HaKlali, and gives some charity. No matter how serious his sins and transgressions, I will do everything in my power to save him and cleanse him. I will span the length and breadth of the Creation for him. By his peyot, his sidecurls, I will pull him out of Hell!’ (Rabbi Nachman’s Wisdom #141).

The practice of visiting the graves of the Tzaddikim to pray is an ancient one, going back to biblical times (Rashi, Numbers 13:22) and was well known in Talmudic times (see Sotah 13a; Zohar II:70b). Even today, many visit the cemetery before the High Holidays, to pray for good health and a successful year. After the death of the Tzaddik, his soul is permanently absorbed in God’s infinity. Since according to the Kabbalah the nefesh, the lowest part of the soul, remains at the gravesite, this is a fitting place for Jews to pray to become attached to the infinity of God. While visiting the graves of Tzaddikim has its definite material benefits, the desire to be a good Jew, to serve God with all one’s heart, is the focal point of the trip to Uman.”

The pilgrimage, also known as the “Rosh Hashanah kibbutz” – kibbutz is a Hebrew word meaning a group or gathering – began shortly after Nachman’s death in 1810. In the days of the Soviet Union, when Uman found itself behind the Iron Curtain, the number of pilgrims was very small though some managed to slip into Uman secretly to worship. After the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, however, the floodgates opened. Today, estimates put the number of pilgrims at as many as 30,000 or more annually.

And as every year goes by, it gets easier and easier for that number to grow. As the pilgrimage has become more routine, so have opportunities for locals in Uman to take advantage of the temporary influx of people and the requisite services needed to support them. As I mentioned above, Uman transforms for this event. Truly. Unlike many cities in Ukraine or around the world that are economically driven by open market commerce – a 24/7/365 phenomenon – the main economic engine in Uman is not traditional commerce but tradition itself. Amazingly, the biggest money-maker in Uman, year in and year out, is Rosh Hashanah.

We drive up to the city and hit a police checkpoint. Corinne is a woman. They are worried we will face trouble with the pious gaggles. Vitaly explains we are American researchers. A-ha! We’re in. The first thing I notice, other than the steady stream of heavily bearded, black-hatted men (can’t miss that, for sure), is the smell and sight of voluminous rubbish. Everywhere. Rosh Hashanah has not begun and the place is already trashed. Now, I realize I am illustrating this as if Uman is always spotless. Like any city, I doubt that that’s true. But I can’t help but wonder how the volume of people and their specific needs, like special meals that must be flown in (Ukrainian cuisine isn’t exactly Kosher), impacts the ability for the city to control waste removal. Frankly, it stinks. We walk uphill and a stream of muddy water trickles down past our feet. I think about public health. I think about the pressure this act of pilgrimage puts on the local community. I think about how, five minutes into our visit, it is abundantly clear that to many, Uman exists as a place of pilgrimage only, and not a home for some 86,000 people year-round.

And then we plunge into the chaos. I experience sensory overload like never before in my life (and that’s on top of the funky stench).

People everywhere. I know these people, like me, are Jewish. But I feel alien. I put on a yarmulke to try to stick out less but really what difference does it make? I have three ear piercings (body modification is technically not allowed in Judaism), I do not have a beard or payot, or unclipped sidelocks, a signature of some ultra-religious Jews. While I know that technically anyone is welcome to participate in the pilgrimage, I feel so completely out of place. The hypermasculine environment, to me, teems with misogyny and homophobia. For the first time in my life, I feel distinctly un-Jewish.

Then there is the cityscape.

Everything from large Soviet-era apartment blocks to small, centuries-old cottages become rental properties for groups of travelers. One man standing outside his house told me that closer to Nachman’s grave, some people will rent their apartments for hundreds of dollars for the week – no small sum in Ukraine, where the average monthly wage is about $200. A monolithic Soviet apartment building is draped in large posters, all of them in Hebrew (or maybe it’s Yiddish). Banners hang over the street advertising every service imaginable: food, lodging, medical help, souvenirs. And all of it, yes all of it, is in Hebrew (….or maybe it’s Yiddish).

The city’s central street, Pushkinska, named for the beloved Russian poet Aleksandr Sergeevich Pushkin, becomes something of a “prayer bazaar.” Large prayer halls, all temporary constructions line the street interspersed with more temporary housing, market stands, a Kosher Pizza Hut, a Kosher knock-off Starbucks, and people shouting words of rabbinic wisdom over megaphones. A man shoves a pamphlet in my face entitled “Don’t Take it Personally.” There’s irony to be found here but I’m not entirely sure what. Local citizens sell SIM cards by the dozens. Electronic dance music (EDM) plays at full volume and I wonder what part of the blaring cacophony is derived from nigun, or traditional Jewish prayer tunes. (Hint: they are likely unrelated.)

Others make bank hauling load after load of luggage for the descending hoards. As the holiday had not yet begun, people were still flowing in off charter buses from airports in Kyiv, Odessa, Lviv, Dnipropetrovsk – great distances to cover after stepping off a flight, especially a transatlantic one. I turn a corner and hear shouting. Aggressive shouting. A man is speaking thickly accented Russian and screaming at a guy, probably my age, who has been hired to push a cart stacked high with bulky suitcases. They are disagreeing over how much he should be paid.

“You said twenty dollars for each of us!” the local fellow shouts as his partner looks on.

“I never agreed to such a thing,” the visitor shouts back. “Twenty for the both of you and that’s it.”

The boy drops the suitcases on the ground. Threats to call the police are volleyed back and forth. They resolve their issues but I begin to understand that there are dynamics at play here that go far beyond the spiritual.

And while I don’t see it myself (or maybe I did), there is prostitution. The righteous many who come to Uman to cleanse their souls prior to facing judgment before God apparently do not consider paying for sex with local women to be forbidden.

I’m going to drop a section of the above-linked article here because I want everyone to read it:

“Wait a moment. What do the rabbis say about hiring sex? It turns out that some rabbis over the ages have ruled that a man may have sex with a woman whom he met in a distant country, on condition they not do it openly, and that he wear black throughout the act in order to be reminded of his shame. Some others have ruled that a man may have sex with an unfamiliar woman if they it is done in secret and nobody can see him.

Daniel, the Breslov who admits to hiring women for sex, says he did get caught by patrols. So what. ‘It wasn’t pleasant but I got over it. I don’t owe any answers to anybody, after all. Only to God.’”

Yep. I’ll let you draw your own conclusions.

But no matter how you shake it, Uman is a special place. It was moving to see so many people engaged in such fervent prayer. I do not consider myself religious but I do find such spiritual depth inspiring (if not perplexing at times). Furthermore, it is likewise moving to see the return of Hasidic tradition to Ukraine after near-total destruction of the Jewish people here. The fact that this is largely imported today, however, is an important distinction to make. Most of the pilgrims are not Ukrainian. Ukraine is merely a platform on which this pilgrimage can take place. The intersection of Ukrainians and Jews is certainly there but it is, for the most part, a fleeting occurrence – and a visibly strained one, at that, no matter how much Uman benefits in positive ways from the event.

I did not spend much time in Uman at all. Roughly two hours after arriving, Vitaly and Corinne got in the car to drive to Odessa and I made my way to the bus station to get back to Kyiv in time for Rosh Hashanah dinner (thank you to Naomi and Geoff, US diplomats, for graciously inviting me into their home for the occasion and for providing much-needed glasses of wine). I hardly spoke to anyone in Uman. I did not really get to the bottom of all of the questions I have. How does this pilgrimage impact the views local, non-Jewish residents of Uman have toward the Jewish people? Where does one draw the line between the necessary right for people to practice their religion or express their faith and providing basic needs for a community that does not participate in such a mass event? And so many other questions.

The answers, I know, are out there and likely very nuanced. I imagine there is a great amount of cooperation between the local administration and pilgrimage organizers to maintain the highest level of mutual respect between locals and visitors. There is also no doubt in my mind that my general distrust of organized religion has colored my opinion and perspective on what I saw that day. And that, perhaps, is unfair to the faithful.

No matter what, I am grateful that I was able to experience such a unique event. For better or worse, my own identity is bound to the Jews of Ukraine like the pilgrims flocking to Uman. At the end of the day, no one can take that away from any of us.

A number of local Jewish organizations and clubs also used this part of the festival to advertise their various programs and activities. On the left, we have Beit Sefer, a group for studying Torah, and on the right, we have Moadim, a youth group that helps participants learn about Jewish holidays. In Ukraine, many people who are Jewish were not raised in religious homes. Freedom of religion did not exist in the Soviet Union and Soviet authorities frequently confiscated religious property as a means of discouraging worship and study. For example, Kyiv’s Brodsky Synagogue, located next to the Fulbright Office, was used as a puppet theater in the USSR.

A number of local Jewish organizations and clubs also used this part of the festival to advertise their various programs and activities. On the left, we have Beit Sefer, a group for studying Torah, and on the right, we have Moadim, a youth group that helps participants learn about Jewish holidays. In Ukraine, many people who are Jewish were not raised in religious homes. Freedom of religion did not exist in the Soviet Union and Soviet authorities frequently confiscated religious property as a means of discouraging worship and study. For example, Kyiv’s Brodsky Synagogue, located next to the Fulbright Office, was used as a puppet theater in the USSR.